Listen to the Zodiac: A to Z podcast “Melvin & Sam: The Strange Saga of a Zodiac Impostor”

On the night of October 11, 1969, the Zodiac murdered cabdriver Paul Stine and removed a portion of the victim’s shirt. Days later, the killer mailed an envelope to the offices of The San Francisco Chronicle. Inside, the Zodiac had included a blood-stained piece of Stine’s shirt along with a letter that traumatized the Bay Area for decades. In his customary cavalier style, The Zodiac wrote, “School children make nice targets. I think I shall wipe out a school bus some morning just shoot out the frunt tire and pick off the kiddies as they come bouncing out.”

The Zodiac’s threat to assassinate school children terrified children and parents everywhere, and created a nightmare of security concerns for police and school officials. Armed men escorted children to and from schools while patrol cars and even aircraft followed along and monitored the surrounding area. As media coverage of Zodiac’s murderous plans became national news and fears of a horrific ambush grew, a local television station was the setting for a chilling scene.

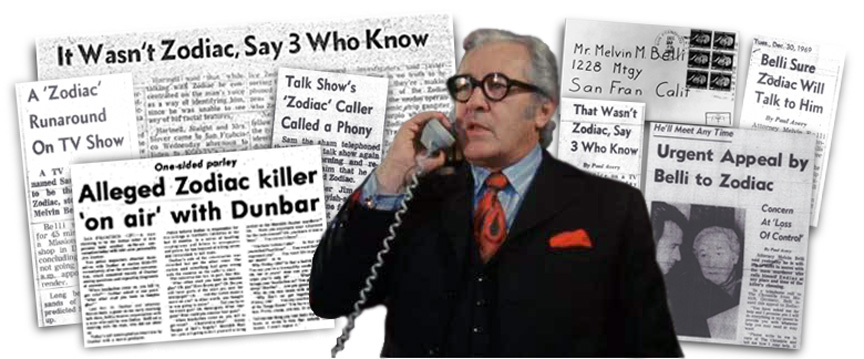

In the early morning hours of October 22, 1969, the Oakland police department received a phone call from a man claiming to be the Zodiac. The caller said he wanted famous Boston attorney F. Lee Bailey to appear on a local television talk show, but told the operator that he would settle for San Francisco lawyer Melvin Belli in the event Bailey was unable to appear.

According to one newspaper article, police reportedly stated that the caller knew unpublicized details about the Zodiac crimes, but this information was quickly contradicted by other news stories stating that police doubted the caller was the Zodiac but proceeded with the television show hoping that the spectacle might expose the imposter and perhaps attract the attention of the real killer.

“SAM” THE SHAM

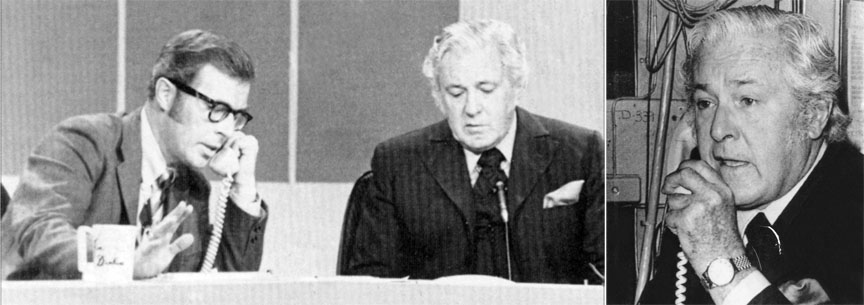

Talk show host Jim Dunbar and attorney Melvin Belli speak with the Zodiac imposter known as “Sam” during a live broadcast at the KGO television station in San Francisco on October 22, 1969.

F. Lee Bailey lived on the East Coast but Belli was a well-known personality in the Bay Area so he was the logical choice to appear on a San Francisco television show on short notice. Hours after the call to Oakland police, Belli was the guest on the show with host Jim Dunbar. A man called the KGO television station several times, and, in conversation with Belli, claimed he was the Zodiac, but he agreed to be called “Sam.” One exchange revealed that Sam had been interested in Belli for some time.

DUNBAR: Talk to us. Just, tell us what’s going on, inside you, right now. Please.

CALLER: I have headaches.

DUNBAR: Right.

BELLI: How long have you had those headaches, uh, Sam? Been a long time?

CALLER: Since I killed a kid.

BELLI: Well, was it before December that you had the headaches?

CALLER: (pause) Yes.

BELLI: If, did, were you in service, that you might have had an injury in service, did you ever fall out of a tree or down stairs? Were you ever unconscious?

CALLER: (pause) I don’t know.

BELLI: You don’t remember. Does aspirin do you any good?

CALLER: No.

BELLI: Doesn’t do you any good?

CALLER: No.

DUNBAR: Sam –

BELLI: Damn stuff never did me any good either.

DUNBAR: Sam, let me ask you a question. Did you, um, did you attempt to call this program one other time when Mr. Belli was with us? And, you called –

CALLER: What?

DUNBAR: Did you try to call us one other time about, oh, two or three weeks ago when Mel Belli was with us?

CALLER: Yes.

DUNBAR: And you, uh, well –

BELLI: You couldn’t get through, and we were talking?

DUNBAR: And you couldn’t get through, the phones were tied up, is that it?

CALLER: Yes.

BELLI: Sam, let me ask you this – There’s some reason why you go to a particular doctor or a particular priest, and some reason why apparently you wanted to talk to me, or Lee? Is it that you feel we have compassion for people who get in trouble? Or, is that you feel that we can do something for you? Or is that you feel we’re, we’re, have enough integrity that if we promise you something, that we’re gonna stick to it?

DUNBAR: Well, let’s find out why he wanted to talk to – Why did you want to talk to Mr. Belli, Sam?

CALLER: I don’t want to be hurt.

BELLI: You’re not going to be hurt. You’re not going to be hurt if you talk to me.

DUNBAR: You’re not going to the gas chamber.

BELLI: I wouldn’t think they’d ask for capital punishment. We should ask the district attorney—you want me to do that, Sam? You want me to talk to the district attorney?

[At this point, Sam screamed.]

BELLI: What was that?

CALLER: I did not say anything. That was my headache.

BELLI: It sounds like you’re in a great deal of pain. Your voice sounds muffled. What’s the matter?

CALLER: My head aches. I’m so sick. I’m having one of my headaches.

[Another scream.]

CALLER: I’m going to kill them. I’m going to kill all those kids!

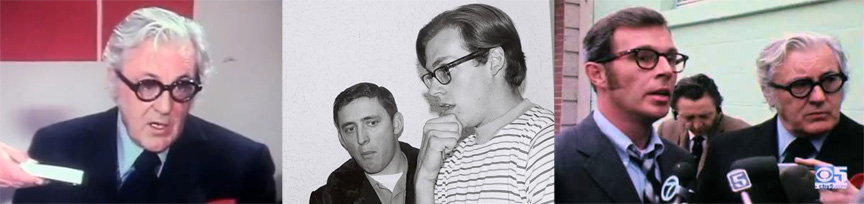

Melvin Belli answers media questions after the broadcast (Left). Napa police officer/dispatcher David Slaight and surviving Zodiac victim Bryan Hartnell listen to the voice of Zodiac imposter “Sam” (Center). Host Him Dunbar and Melvin Belli talk to reporters (Right).

During a private conversation off-the-air, Belli asked Sam to meet in-person and suggested a church in Chinatown as the location. Sam reportedly replied, “Meet me on top of the Fairmont Hotel. Without anybody else. Or I’ll jump.” Belli and Sam eventually agreed to meet at thrift store in Daly City, but when the attorney and a crowd of police officers, reporters, and onlookers gathered at the agreed location, no one was surprised that Sam failed to appear.

Police tried to trace Sam’s calls to the KGO switchboard but the caller thwarted their efforts by repeatedly hanging up and calling back. Investigators did not believe that Sam was the real Zodiac but he had to be identified and located nonetheless. The Oakland police dispatcher who answered the call from the person who claimed to be the Zodiac stated that Sam was the same caller. The three people who had spoken to the Zodiac also listened to Sam’s voice. Surviving Zodiac victim Bryan Hartnell, Vallejo police dispatcher Nancy Slover, and Napa police dispatcher officer David Slaight all agreed that Sam was an imposter. Bryan recalled that the man he had encountered at Lake Berryessa seemed older and had a deeper voice. Officer Slaight agreed and said that Sam was too young to be the man who called the Napa Police Department. Nancy Slover thought that Sam was “too pitiful and pathetic to be Zodiac.” A San Francisco Chronicle article referred to the caller as “Sam the sham.”

MURDER AT ALTAMONT

Advertisements for the Rolling Stones concert film GIMME SHELTER read, “The music that thrilled the world… and the killing that stunned it!” In film footage, Meredith Hunter is seen moving through the audience with a gun. A member of the Hell’s Angel biker gang stabbed and killed Hunter.

In the weeks after his televised phone conversations with “Sam,” Melvin Belli worked with rock legends The Rolling Stones as they attempted to find a concert venue somewhere in San Francisco. Belli worked as mediator between The Stones and Dick Carter, the owner of the Altamont Speedway. (These conversations and other footage featuring Belli and the band members can be seen in the 1970 film Gimme Shelter.)

On December 6, 1969, crowds gathered at the site of the concert at the Altamont Speedway. Melvin Belli arrived and made his way through the mass of spectators. The infamous motorcycle gang The Hells Angeles served as security, reportedly in exchange for large quantities of beer, and gang members were involved in various hostile and violent incidents with fans throughout the concert. Fans were shocked when Alan Passaro, a 21 year-old Hells Angel, stabbed a man as the band played on. When the man died, the brutal stabbing quickly became a media nightmare for The Rolling Stones, and a serious legal problem for The Hells Angels. The concert had been recorded on film as part of the upcoming movie, Gimme Shelter, and the film revealed that the victim had pointed a gun at lead singer Mick Jagger before the Hell’s Angel intervened.

A few days after the December 6 concert, the district attorney called Dick Carter, the owner of the Altamont Speedway, and informed him that Carter and the Hell’s Angels would face charges in the killing of the gunman. Carter then called members of the Hell’s Angels in an attempt to locate the missing gun used by the victim. Carter hoped the gun and the concert footage would prove that Alan Passaro had acted to protect Jagger and others from the gunman and, therefore, should not face charges.

Once the Angels located the weapon, Carter contacted attorney Melvin Belli, who had helped the Rolling Stones arrange the concert at the speedway. Belli told Carter to put the gun in a shoebox and bring it to his office. Carter followed Belli’s instructions and took the weapon to Belli’s San Francisco office. While Belli was able to help the gang members temporarily avoid prosecution, the district attorney later filed first-degree murder charges against Alan Passaro. (A jury acquitted Passaro in January 1971, and concluded that he had acted in self-defense.)

DEAR MELVIN

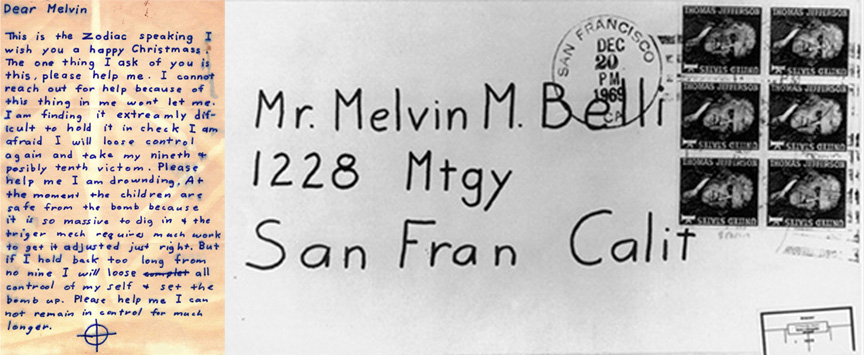

Melvin Belli left San Francisco on December 20, 1969, to attend a conference of military trial lawyers held in Munich, Germany. On that same day, the Zodiac mailed a letter to Belli’s home. Postmarked December 20, the envelope arrived at the attorney’s residence on December 23. Belli’s housekeeper then forwarded the envelope to the attorney’s office. After the Christmas holiday, office employees opened the envelope and found it contained a written plea for help and a blood stained scrap of cloth. Belli’s staff immediately notified the San Francisco Police department. Handwriting experts concluded that the Zodiac had written the letter, and police confirmed that the scrap of cloth did, in fact, come from the shirt worn by the Zodiac’s last known victim, cabdriver Paul Stine. The Zodiac seemed to have commented on the Zodiac imposter “Sam” by sending a letter to Belli along with a piece of a victim’s clothing, as if to say, “That other person is an imposter. I’m the real Zodiac.”

The Zodiac letter and envelope sent to Melvin Belli after the attorney’s televised conversation with Zodiac imposter “Sam.” The letter was accompanied by a piece of victim’s clothing to establish that the writer was the killer and not an imposter.

San Francisco Chronicle reporter Paul Avery contacted Melvin Belli by telephone in Munich, Germany on December 28. Belli commented on the Zodiac letter and offered his help to the Zodiac. Avery’s article appeared in The San Francisco Chronicle on December 29, 1969, and specifically stated that Belli was “en route to Germany” on the day the letter had been postmarked – December 20, 1969. Avery also mentioned that the housekeeper had forwarded the letter. Belli described his travel plans to Avery, who wrote, “Belli said he is scheduled to remain in Europe for several weeks – he has a trial starting next week in Naples, and then plans to fly to Algiers (Africa) to confer with fugitive Black Panther Eldridge Cleaver …

Belli made several public appeals asking the Zodiac to turn himself into authorities with the promise that the attorney would protect the killer and help him avoid the death penalty. According to all of the available evidence, including police reports, FBI files, official documents, and interviews with investigators, the real Zodiac never contacted Belli again, but the man who called the Jim Dunbar show had apparently developed an obsession with the celebrity lawyer.

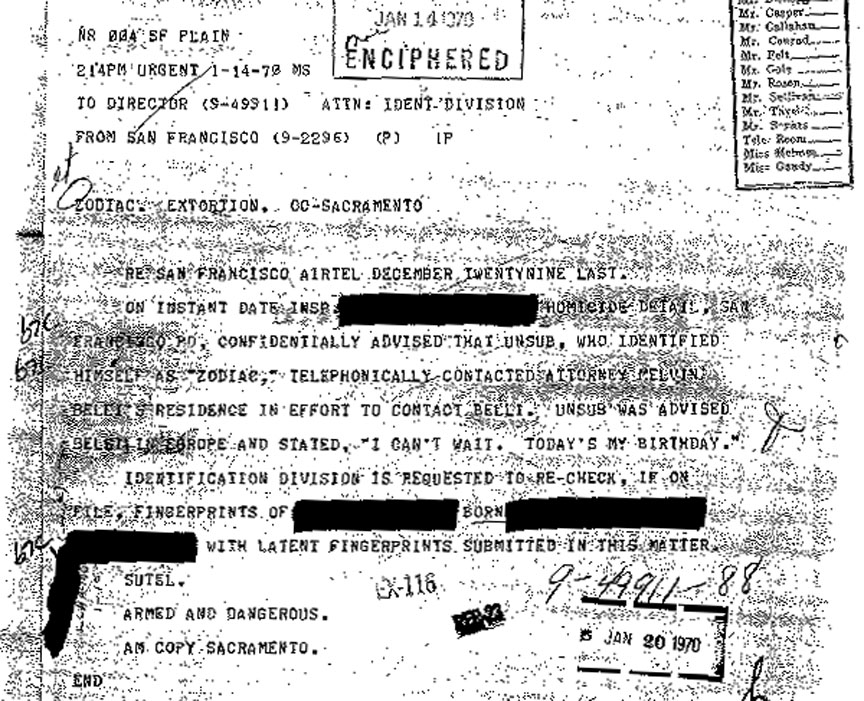

On January 14, 1970, SFPD Inspector William Armstrong contacted the FBI to report that someone claiming to be the Zodiac had called the home of Melvin Belli and asked to speak with the famed attorney. The report read:

1 14 70 RE: SAN FRANCISCO AIRTEL DECEMBER TWENTY NINE LAST. On instant date Insp. (name redacted), Homicide Detail, San Francisco Police Department, confidentially advised that UNSUB, who identified himself as ‘Zodiac,’ telephonically contacted attorney Melvin Belli’s residence in effort to contact Belli. UNSUB was advised Belli was in Europe and stated, ‘I can’t wait. Today’s my birthday.’

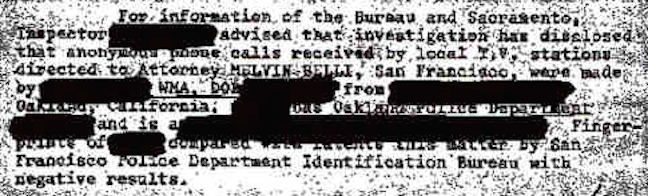

An FBI report dated January 14, 1970, documents the telephone call to Belli’s home by the Zodiac imposter.

This report was marked “URGENT” and directed to the “Identification Bureau.” According to the report, San Francisco police requested that the FBI “re-check” the fingerprints of a suspect who had previously been reported to the Bureau, suggesting that the birth date of the caller was the same as the date the call had been made. The name, and birth date of the suspect, were redacted before the report was released to the public, leading to speculation regarding the actual date of the call. The first line of the report read, “RE: SAN FRANCISCO AIRTEL DECEMBER TWENTY NINE LAST,” and has been misinterpreted as the date that San Francisco police notified the FBI regarding the “birthday” call. Each FBI report includes the date of the last report referencing the same subject matter. On December 29, San Francisco police contacted the FBI to report the Zodiac’s most recent attempts to contact Melvin Belli by mail. Per FBI procedure, the next report to reference the Zodiac’s possible attempts to contact Belli cited the most recent report previously filed on the subject.

The report stated that the FBI was contacted by San Francisco police “On instant date.” This term is used in official documents to quickly and clearly denote the current date, time, or subject – in short, “instant date” translates to today’s date. The report is dated January 14, 1970, indicating the “birthday call” took place on or shortly before January 14, 1970. The language of the report clearly indicates that San Francisco police contacted the FBI on the instant date, January 14, 1970, to report information about a telephone call to Belli’s home which occurred on January 14, 1970, or shortly before that date.

FBI files indicated that police were quick to report developments to the FBI. The SFPD sent dozens of requests to the FBI for assistance in the investigation, including fingerprint and handwriting comparisons, checks for criminal records, identifications of suspects, suspect information, examination of coded messages, and more, including simple memos to correct the spelling of a suspect’s name. In one instance, police requested copies of the fingerprints belonging to a potential suspect and arranged with the FBI for the evidence to be flown from Washington to California on the same day the request was submitted. The evidence indicated that police would not delay reporting an event as significant as the killer declaring his date of birth.

The “birthday” call inspired police to set up a trace on Belli’s home phone in the hopes that future calls from the Zodiac imposter would lead to his location and identity. On February 5, 1970, the KGO television station received another call from a man who claimed to be the Zodiac. Host Jim Dunbar spoke with the caller but the man’s voice was not broadcast on the air. Like Sam, the caller complained about headaches and said that he did not want to be harmed. The man stated that he was eighteen years old, admitted that he sniffed gasoline and glue to get high, and confessed that he possessed at least four guns. The caller allegedly stated that he wanted Melvin Belli to represent him and made statements indicating that he was allegedly seeking justice for Meredith Hunter, the man killed by a member of the Hell Angels biker gang during the Rolling Stones concert at the Altamont Speedway in December, 1969. Belli had represented the Rolling Stones in negotiations with Altamont owner Dick Carter and then assisted the Hell’s Angels after Hunter’s death. The caller’s interest in the Altamont incident served as further evidence that he was focused on Melvin Belli.

The February 6, 1970 edition of the San Francisco Chronicle featured the headline, “Talk Show’s ‘Zodiac’ Caller Called a Phony” and reported, “Sam the sham called that KGO talk show again yesterday morning and repeated his claim that he is the killer called Zodiac… Homicide detectives later listened to a tape recording of the conversation and concluded that ‘Sam’ was a phony.” SFPD Inspector Toschi listened to a recording of the caller’s voice and offered his opinion, “It most certainly was not Zodiac.” Toschi and his partner William Armstrong had been searching for the elusive “Sam” since the television spectacle with Melvin Belli in October, 1969. Police were unable to trace Sam’s calls to the KGO station but they placed a trace on Belli’s telephone line after Sam started calling the attorney’s home.

An excerpt from an FBI report dated February 18, 1970, documents the identification of the Zodiac imposter “Sam.”

On February 18, 1970, San Francisco police contacted the FBI to report that the individual who had been calling Belli at the television station had been identified and located. The report read, “For information of the Bureau and Sacramento, Inspector [REDACTED] advised that investigation has disclosed that anonymous phone calls received by local T.V. stations directed at Attorney MELVIN BELLI, San Francisco, were made by [REDACTED], WMA, DOB [REDACTED], from [REDACTED] Oakland, California.” The report also stated that the man’s fingerprints were “compared with latents this matter by San Francisco Police Department Identification Bureau with negative results.” The calls had been placed from a mental institution, and the caller, who had used the names “Sam” and “The Zodiac,” was actually a patient.

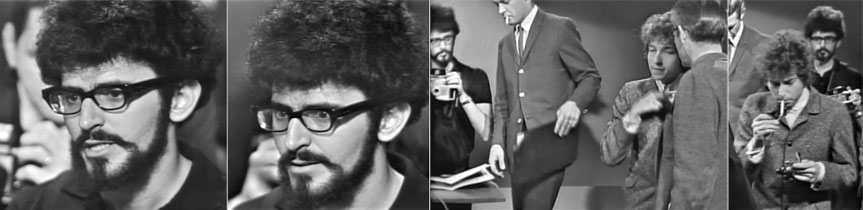

PLAY IT AGAIN, SAM

The identity of “Sam” had been redacted from the FBI files released to the public, but a report written by former San Francisco Chronicle reporter Paul Avery identified the man as “Eric Weil.” Available information indicates that Avery had misspelled the man’s named, and the individual in question was named Eric Weill. An amateur photographer, Eric Weill lived in the Bay Area during the 1960s. “By all accounts, Eric was just one of those guys who showed up everywhere with a camera,” wrote a former acquaintance. “My efforts to track down Eric were unsuccessful. One person I interviewed was pretty sure Eric ended up doing time in prison not long afterwards.”

On December 3, 1965, songwriter and rock legend Bob Dylan appeared at a press conference held in the studio of San Francisco television station KQED and hosted by the music lover, Ralph J. Gleason. Eric Weill attended and took photographs with a Polaroid camera throughout the event. As the conference began, Weill had an odd question for Dylan.

GLEASON: Who’s first? Come on.

WEILL: I’d like to know about the cover of your, of your forthcoming, or your, uh, uh, album – the one with Subterranean Homesick Blues in it. I’d like to know about the, the meaning of the photograph with you and the wearing of the “Triumph” tee-shirt.

DYLAN: What did you want to know about it?

WEILL: Well, that, you know, that, that’s an equivalent photograph, it means something, it’s got a philosophy in it – (audience laughs; Dylan is amused) – and I’d like to know visually what it represents to you, because you’re a part of that.

DYLAN: (searching for an answer) I haven’t really looked at it that much, I don’t really –

WEILL: (emphatically) I’ve thought about it a great deal.

DYLAN: All right, it was just taken one day when I was sitting on the steps, you know. I don’t, uh, I don’t really remember, really, uh, too much about it.

WEILL: What about the motorcycle as an image in your, in your songwriting? You seem to like that.

DYLAN: Oh, well, we all like motorcycles, to some degree.

WEILL: (quietly) I do.

Immediately after the conclusion of the press conference, Eric Weill stepped onto the stage right behind Bob Dylan and began taking photographs. He tried to follow the singer until a crowd formed and blocked his path. Weill’s fascination with celebrity was evident during the 1965 press conference and during his 1969 telephone conversation with Melvin Belli on KGO television. Speaking as “Sam,” Weill admitted to TV host Jim Dunbar that he had previously attempted to call the television station during Belli’s appearance on the program several weeks earlier. The man who called Dunbar’s show on February 5, 1970, also mentioned Belli and his connection to the events surrounding the murder at the Altamont Speedway. Weill’s behavior indicated that he had become fixated on Belli, and that the calls to Belli’s home were part of his ongoing efforts to establish contact with the celebrity lawyer.

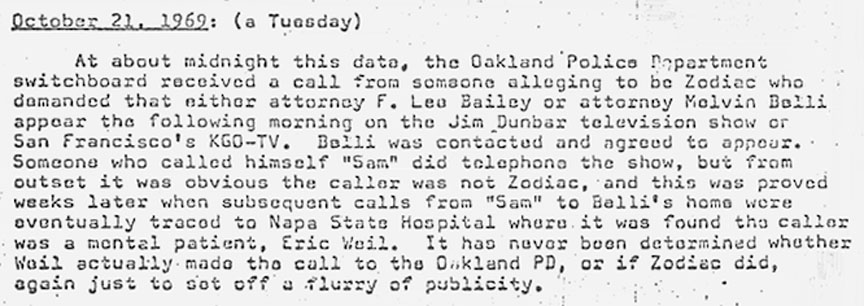

An excerpt from a 1971 report written by San Francisco Chronicle reporter Paul Avery describes the events surrounding the telephone calls from Zodiac imposter “Eric Weil” aka “Sam.”

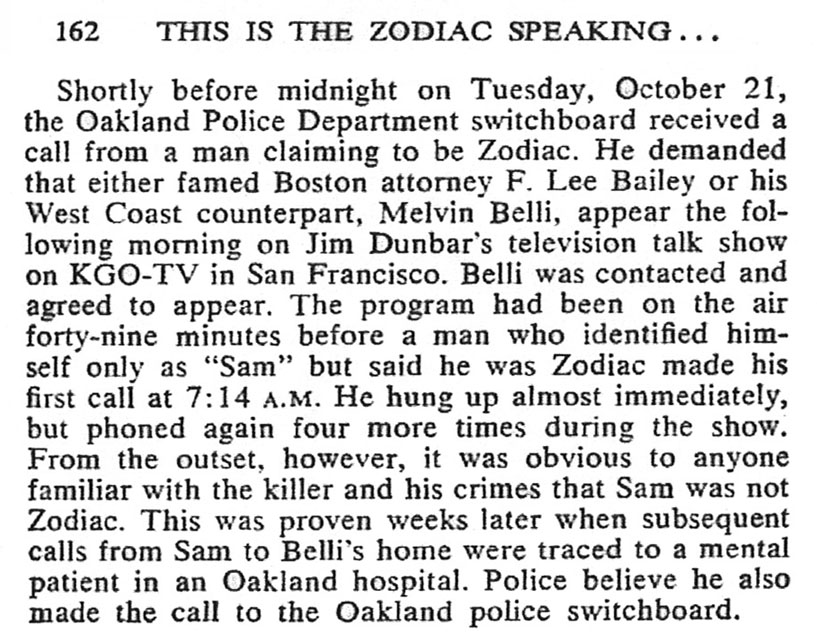

In his 1971 summary of the Zodiac case, reporter Paul Avery wrote that “Eric Weil” had been identified after calls to Belli’s home were traced to the mental hospital. In his 1975 book, Great Crimes of San Francisco, San Francisco Chronicle reporter Duffy Jennings quoted from Avery’s report and stated that police had been able to locate “Sam” after calls to Melvin Belli’s home were traced to a mental hospital. Avery’s report stated that Sam was traced to Napa state hospital but Jennings stated that Sam was traced to a mental hospital in Oakland. Jennings wrote that police believed the imposter had been responsible for the calls to the television station as well as call to the Oakland police department in October. San Francisco investigators cleared Eric Weill as a Zodiac suspect.

An excerpt from the book GREAT CRIMES OF SAN FRANCISCO by San Francisco Chronicle reporter Duffy Jennings describing the events leading up to the identification of Zodiac imposter Eric Weill aka “Sam.”

The FBI report was the only official document to mention the so-called “Zodiac birthday call” to Belli’s residence. The call was not mentioned in any of the hundreds of pages of reports produced by the Vallejo police department, the Napa County Sheriff’s Office, the Department of Justice or the San Francisco police department. If authorities had any reason to suspect that the real Zodiac was responsible for the birthday call, the important information regarding the killer’s possible date of birth would most likely appear somewhere in the official files generated during the decades of investigation. The available police reports, FBI files, and other official documents make no mention of this seemingly important information regarding the Zodiac’s identity.

ANATOMY OF A MYTH

The fact that someone claiming to be the Zodiac had placed a telephone call to Melvin Belli’s home and revealed his date of birth was not disclosed to the public until 1999, when FBI files regarding the Zodiac case were released through the Freedom of Information Act. Prior to the release of these documents, the so-called “Belli birthday call” had never been reported in any other official documents, FBI files, police reports, news stories, books, or other accounts of the case. None of the investigators ever referred to the call in interviews with reporters, researchers, and others. By all accounts, the man who called The Jim Dunbar Show to talk with attorney Melvin Belli was universally known as an imposter.

The facts demonstrated that the man who called the Dunbar show was identified by investigators who determined that he was not the Zodiac, but several myths developed around this relatively minor event in the Zodiac story. These persistent myths claimed that the real Zodiac had placed the telephone calls to the television station and to Belli’s home, that the “Belli birthday call” occurred on December 18, 1969, and the man identified as “Sam” was not the same person who spoke to Dunbar and Belli during the television broadcasts. These myths were debunked by the facts but served a purpose for many aspiring Zodiac theorists offering theories about the case and accusing suspects.

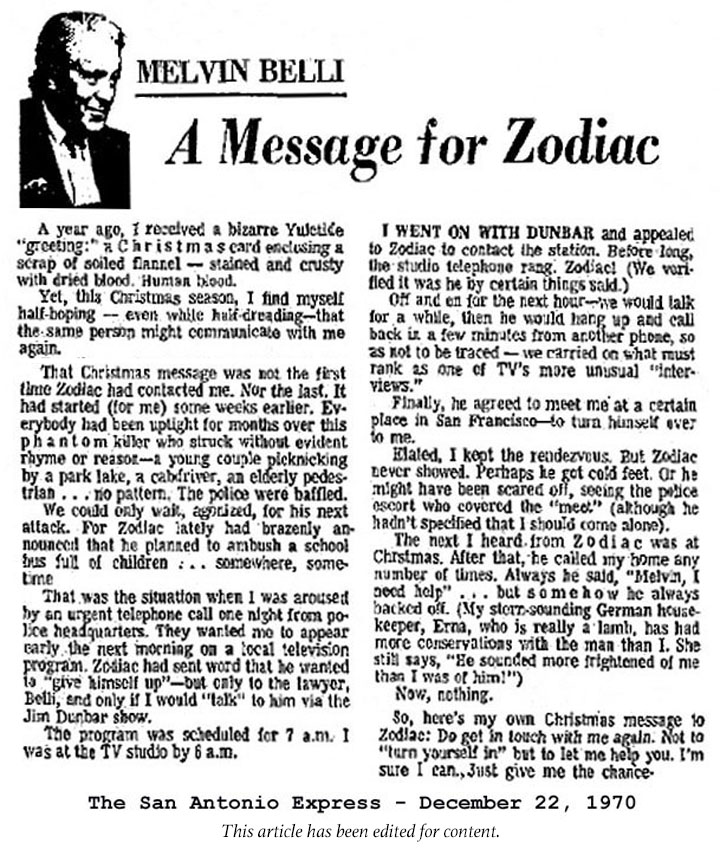

Melvin Belli contributed to the confusion regarding these events with conflicting and changing versions of his story over the years. In an article written for the San Antonio Express and published on December 22, 1970, Belli wrote, “A year ago, I received a bizarre Yuletide ‘greeting:’ a Chrismas card enclosing a scrap of soiled flannel— stained and crusty with dried blood. Human blood.” The Zodiac sent a letter, not a card, and the piece of cloth was from a white shirt with dark stripes, not flannel as Belli wrote. Belli’s account confused matters by claiming that the man who called the Dunbar show was the real Zodiac. “That Christmas message was not the first time Zodiac contacted me. Nor the last. It had started (for me) some weeks earlier.” Belli’s timing of events was in keeping with the known facts despite his inaccurate statements concerning the caller’s identity. “The next I heard from Zodiac was at Christmas. After that, he called my home any number of times. Always he said, “Melvin, I need help”… but somehow he always backed off.” Belli ended the article with another plea asking Zodiac to contact him.

Belli’s timing of events was accurate when he stated that he “heard” from Zodiac “at Christmas,” a reference to the Zodiac letter postmarked December 20, 1969, delivered to his home on December 23, and forwarded to his office on December 26, the day after Christmas. Belli seemed to believe that he had spoken to the real Zodiac during the broadcast of the Jim Dunbar show, but the FBI files stated that this man had been identified and was not the Zodiac. Belli seemed to be unaware that police had located and identified the man who had called his home and the television station. The possibility existed that Belli was trying to enhance his connection to the real Zodiac by insisting that the killer was also responsible for the calls to his home.

Melvin Belli often misstated the facts when attempting to recall events and dates but some of his statements were in keeping with the known facts. Belli wrote that the “Zodiac” called his home AFTER the letter sent to the attorney “at Christmas,” dating the first calls to his home after December 25 and after the arrival of the Zodiac letter at his office on December 26. According to Belli’s timing of events, the “Zodiac” called his home after December 18, 1969. In his book, My Life on Trial, Belli wrote that the Zodiac sent him a “brief note on December 18,” and then stated that the “Zodiac” had called his home several times after that date.

Both of Belli’s written accounts contradicted the account and timing presented in the books written by former San Francisco Chronicle cartoonist Robert Graysmith. Graysmith’s 2002 book, Zodiac Unmasked, cited the FBI report by number 9-49911-88 and claimed that the “birthday” call was made by the real Zodiac on the December 18, the birthday of his chosen suspect, Arthur Leigh Allen. On page 324 of his book, Graysmith wrote: “Recall that on Thursday, December 18, 1969, Zodiac rang the attorney’s housekeeper and remarked that today was his birthday. Two days later, December 20, a letter from Zodiac arrived at Belli’s office. The FBI quoted that conversation in report 9-49911-88.” Graysmith then tried to link the call to his pet suspect and added, “December 18 was Arthur Leigh Allen’s birthday.”

The FBI report cited by Graysmith did not state that the telephone call to Belli’s home had occurred on December 18, 1969. The FBI reports indicated that the telephone call occurred almost one month later in January 1970. The Zodiac letter did not arrive at Belli’s office on December 20, 1969, two days after the phone call as Graysmith claimed. The Zodiac letter was delivered to Belli’s home and not to his office as Graysmith claimed, and the letter arrived on December 23, 1969, and not on December 20, as Graysmith claimed. The letter was forwarded to Belli’s office and arrived after Christmas day on December 26. The facts demonstrated that Graysmith’s account was inaccurate and false.

The “birthday” call to Belli’s home was not attributed to the real Zodiac until Graysmith did so in this book. Graysmith was also the first and only person to claim that the call had occurred on the birthday of his suspect. Graysmith’s accounts of the call varied. On page 362 of Zodiac Unmasked, under the date “Thursday, December 18, 1969,” Graysmith wrote, “Zodiac called the attorney’s home, but got his housekeeper instead.” Graysmith cited the lone FBI report, #9-49911-88, dated January 14, 1970, as the source for his date of the call. Under the date “Saturday, December 20, 1969,” Graysmith wrote, “Two days after the call, exactly a year after the first Northern California murders, Zodiac’s letter containing a square of Stine’s bloody shirt arrived at Belli’s home. Unopened, it was forwarded down to his business office to be opened by his secretary.” On page 365, Graysmith wrote, “… December 20, a letter from Zodiac arrived at Belli’s office.”

Graysmith provided a quote from Belli’s book, My Life on Trial, on page 363 of Zodiac Unmasked. “On December 18, 1969, the Zodiac mailed me a brief note wishing me a happy Christmas. I went off to safari in Africa. But while I was there, the Zodiac, according to my housekeeper, phoned me several (more) times.” Graysmith inserted the word “more” into Belli’s quote to imply that Belli had mentioned a previous call when, in fact, he did not do so. Belli (erroneously) referred to a “note” from Zodiac on December 18 and not a telephone call on that date.

Belli dated the note on December 18 but did not provide the date of the phone calls. He stated that he was “off to safari in Africa” while the Zodiac was phoning his home. Belli’s timing of the event indicates that he did not leave San Francisco until after the Zodiac had mailed the letter on December 20, 1969. Belli’s statement, made long after the time in question, indicates he may have been confused about where he had traveled at the time, but his statement that he left after the Zodiac mailed the letter is consistent with the account of his travel plans provided to reporter Paul Avery in December 1969.

Using the available information, the following timeline accounts for Belli’s whereabouts in late 1969 and early 1970:

Dec 6 thru Dec 20 = San Francisco

December 20, 1969 = Belli departs for Europe

Dec 20 thru Dec 28 = Munich, Germany

Dec 28 thru Jan 2/3 = Munich, Germany

Jan 2/3 thru Jan 9/10 = Naples, Italy

Jan 9/10 thru Jan 14/on = Algiers, Africa

This rough estimate placed Belli in San Francisco until December 20, when he departed for Europe. Belli remained in Europe until he left for Africa some time in the second or third week of January.

If Belli was correct, and the calls to his home were placed while he was in Africa, the calls took place some time in the second or third week of January of 1970. The only FBI report to mention this birthday call is dated January 14, 1970, or the end of the second week of January.

Graysmith wrote that Belli had returned to California after he had been in Naples. According to Belli’s statements to Paul Avery, he was scheduled to be in Naples during the first week of January 1970. Belli also said that the Zodiac calls had occurred after he had arrived in Africa. Belli was scheduled to be in Africa sometime during the second or third week of January 1970. If Belli had returned to California he must have done so sometime in the middle of January before he traveled to Africa.

All of the available information indicated that the “birthday” call to Belli’s home occurred shortly before or on January 14, 1970. None of the available information indicated the call occurred on December 18, 1969.

REVISIONIST HISTORY

Graysmith’s books served as the basis for a new film directed by David Fincher (Se7en). In the film, the so-called “Zodiac birthday call” serves as a lynchpin of Graysmith’s accusation that his suspect, Arthur Leigh Allen, was the Zodiac. In order to lend credence to the false narrative that the person who called Belli’s home was the real Zodiac, the film changes the facts to suit its needs. In the fictional story of the film, the police trace Sam’s calls on the day of the Jim Dunbar broadcast on October 22, 1969, to a mental hospital and immediately identify the caller as an imposter. In the film, on the same day of the Dunbar broadcast and failed meeting with “Sam,” SFPD Inspector William Armstrong tells his partner David Toschi, “They pulled off the trace. Our Daly City no-show called from a mental institution.” In reality, police were unable to trace the calls that day and did not locate the caller at a mental institution until three months later. The film also leads audiences to believe that the real Zodiac called Belli’s home on December 18, 1969, despite the facts which contradicted that version of events. In order to create the false illusion that the real Zodiac was involved, the film portrays Armstrong’s character stating a falsehood. “The Oakland PD operator is sure the man she talked to had a deeper voice, calmer. It might have actually been him.” The film implies that “him” was the real Zodiac by creating the false narrative that the Oakland PD operator who answered the first call from the person claiming to be the Zodiac did not believe that the person who called the Jim Dunbar show was the same person who called the Oakland police department. In reality, the Oakland police operator believed that “Sam” was the same person who called the Oakland police department, raising questions about the motives behind the decisions to fill this scene in the film with fiction seemingly designed to mislead viewers into believing two different callers were involved— a Zodiac imposter and the real Zodiac.

A recreation of the Jim Dunbar show from the 2007 movie ZODIAC. In another fictional scene, San Francisco police inspector William Armstrong (actor Anthony Edwards) states that the calls to the KGO television station by “Sam” were made by a mental patient.

The filmmakers used the actual video tapes of the original television broadcast as the source for the film’s recreation of the Jim Dunbar show, going so far as to reproduce the set, the clothing, and much of the dialogue from the original broadcast. However, the filmmakers made a deliberate decision to alter the dialogue during one specific segment in order to further the false narrative that two different people were making “Zodiac” telephone calls. In reality, host Jim Dunbar asked “Sam” if he had called in to the television show during a previous broadcast featuring Melvin Belli.

DUNBAR: Sam, let me ask you a question. Did you, um, did you attempt to call this program one other time when Mr. Belli was with us? And, you called –

SAM: What?

DUNBAR: Did you try to call us one other time about, oh, two or three weeks ago when Mel Belli was with us?

SAM: Yes.

DUNBAR: And you, uh, well –

BELLI: You couldn’t get through, and we were talking?

DUNBAR: And you couldn’t get through, the phones were tied up, is that it?

SAM: Yes.

In the fantasy version of reality written by screenwriter Jamie Vanderbilt, the same sequence had been changed as follows:

DUNBAR: “Did you attempt to call one other time when F. Lee Bailey was with us two or three weeks ago?”

SAM: “Yes.”

DUNBAR: “And why did you want to talk to Mr. Bailey?”

BELLI: “Why do you wanna talk to me, Sam?”

[Here, Dunbar is shown looking at Belli as if he disapproves of the attorney’s attempt to focus on himself.]

The filmmakers altered the dialogue in this scene, changing the name “Mel Belli” to “F. Lee Bailey.” The individual who originally called the Oakland police department had claimed to be the Zodiac and demanded that Belli or Bailey appear on Dunbar’s program. However, Dunbar himself referred specifically to “Mel Belli” as the guest on a previous show and “Sam” replied that he had tried to call during that specific program to talk to Belli and not F. Lee Bailey. Belli himself confirms that he was a guest on a previous show by saying, “You couldn’t get through, and WE were talking?”

In reality, Dunbar had asked “Sam” if he had tried to call during a previous broadcast featuring Melvin Belli, and Sam replied, “Yes.” In the film’s version of the same dialogue, Dunbar’s character asked Sam if he had tried to call during a previous broadcast featuring F. Lee Bailey, and Sam replied, “Yes.” Given the undeniable fact that the film makers had access to the actual video of the original broadcast, the change in the dialogue stands out as a deliberate decision. The film already tried to create the false impression that two different people had called in to the Dunbar show– the Zodiac imposter and the real Zodiac. Later, the film makers tried to create the false impression that the real Zodiac had called Belli’s home on Allen’s birthday. In reality, Sam/Eric Weill confessed that he called during Belli’s previous appearance on Dunbar’s show, and, the calls to Belli’s home were traced to a mental hospital and Eric Weill. The real-life facts demonstrated that Zodiac imposter Eric Weill had an apparent obsession with Belli which drove him to call the attorney. The film tried to obscure the evidence of Weil’s obsession with Belli by creating the false impression that the Zodiac imposter was fixated on F. Lee Bailey, instead. This change set up the film’s later false claim that the real Zodiac called Belli on Allen’s birthday. In short, this change created the false impression that the Zodiac imposter was interested in Bailey and the real Zodiac was focused on Belli.

In this fictional scene from the movie ZODIAC, Melvin Belli holds a Zodiac letter in his barehands and informs SFPD inspectors Armstrong and Toschi that the killer called his home.

Facts were changed and the events were rearranged to accommodate the film’s false narrative regarding Belli’s whereabouts at the time of the Zodiac letter sent to his home. One curious scene shows Toschi and Armstrong arriving at the home of Melvin Belli while Christmas music plays. Inside, they find the melodramatic attorney sitting behind his desk and holding a new letter from the Zodiac. Belli reads the letter to the inspectors who are not happy with him. Belli says that the people have a right to know about the letter and Toschi says, “Which is why you contacted the Chronicle.”

Armstrong asks when the letter arrived and Belli says that the envelope came during “the middle of last week.” He believed that the Zodiac had chosen to write to his home because he had been unable to contact Belli at the TV station or “here,” meaning Belli’s home. Armstrong asks, “He tried to contact you here?” Belli responds, “Several times,” and explains, “I was out but he spoke with my housekeeper.” Armstrong then runs off to question the housekeeper.

The facts demonstrate that Belli was in Munich, Germany, and not in San Francisco, when the Zodiac’s letter arrived at this home on December 23, 1969. He was not at his home and did not touch the Zodiac letter, nor did he contact the Chronicle before alerting authorities. Belli did not tell police about phone calls to his home because no such calls had occurred at that time. According to the FBI files, Belli’s housekeeper did not report receiving any phone calls from someone claiming to be the Zodiac at the time in question but she did so later in January 1970.

Immediately after this scene of the film, a title on the screen reads, “March 22, 1970 – 2 1/2 Months Later.” Approximately 2 1/2 months before March 22, 1970 would date the scene in Belli’s home in the second week of January, or the time of the FBI report which mentioned the “Zodiac birthday call.” In the film’s bizarre, fact-free version of events, the Zodiac letter arrived at Belli’s home one week before his meeting with Toschi and Armstrong in the second week of January 1970, almost three weeks after the Zodiac letter was actually sent.

In another scene, Graysmith sits in the home of Melvin Belli, waiting to meet with the famous attorney. Melvin’s housekeeper brings the cartoonist some refreshments while he moans about the length of his wait. He tells her that he is writing a book about the Zodiac case and the housekeeper says, “I talked to him.” Graysmith asks, “With Mr. Belli, about the case?” and the housekeeper replies, “With Zodiac, when he called.” She tells Graysmith that the caller had said it was his birthday. When asked to recall the date of the phone call, the housekeeper says, “Mr. Belli was away for Christmas, gone for a week…then the letter arrived.” She further states that Belli “came back on Christmas.” Graysmith deduces, “So, the call came before December 20,” and says to himself, “So, he (Belli) left on the 18th.” The scene reveals that Graysmith’s character has invented the December 18 date by necessity with a clear bias against his suspect regardless of the facts.

Graysmith never interviewed Belli’s housekeeper, and he did not learn of this so-called “birthday” call until 1999 with the release of the FBI files on the Zodiac case. These files demonstrates that the telephone calls to Belli’s home occurred in early 1970, and that these calls were traced to the patient in a mental hospital. Belli did not leave for Europe on December 18, but on December 20, as he told reporter Paul Avery. Belli was not in San Francisco for Christmas as the housekeeper described in the film, but in Munich, Germany, as is well documented in press accounts of that time.

After the scene with Belli’s housekeeper, the film shows Graysmith as he breathlessly dials Toschi for confirmation on the “birthday” call. Toschi is evasive but then tells the cartoonist that, had his partner checked on the call, he would have to “put that in a report” for the Department of Justice. Any reports Armstrong filed with the Department of Justice would have stated that the telephone calls to Belli’s home were traced to a mental patient and were not made by the real Zodiac, as the San Francisco police department had reported to the FBI in February 1970. Toschi therefore had no reason to tell Graysmith otherwise.

Graysmith is also shown speaking with Agent Mel Nicolai of the State Department of Justice in Sacramento, California. Nicolai states that none of the suspects had been born on December 18, the day Graysmith believes the “birthday” call took place. Nicolai says, “Armstrong checked this out.” Had Armstrong “checked this out,” he would have known that his own suspect, Arthur Leigh Allen, was born on December 18. Obtaining a suspect’s date of birth and other vital statistics is usually the first thing on an investigator’s list of things to do. Even within the confines of the film’s fictional universe, the inconsistent narrative indicates that none of the characters/investigators seemed to notice this important fact, indicating that even they knew that the “birthday” call did not take place on December 18, and they considered the call to be of no importance in the investigation.

Near the end of the film, Robert Graysmith appears at the home of SFPD Inspector David Toschi, proudly produces Arthur Leigh Allen’s drivers license and cites the December 18 “birthday” call to attorney Melvin Belli. Toschi seems impressed by Graysmith’s discovery concerning Allen’s date of birth and the date of the “birthday” call. In reality, Toschi knew that the “birthday” call did not occur on December 18, and that the caller was a patient in a mental hospital, not the Zodiac.

INESCAPABLE CONCLUSIONS

Decades of misinformation spawned years of confusion, falsehoods, and myths regarding the events surrounding The Jim Dunbar show on October 22, 1969, and the identity of the caller known as “Sam.” Popular books and films led the public to believe that the caller was the real Zodiac, but the facts led to several inescapable conclusions:

– The man who called the TV station on October 22 and spoke with Melvin Belli by phone was not the Zodiac, but Eric Weill.

– The real Zodiac mailed a letter to Belli’s home on December 20, 1969, the day that Belli departed for Europe.

– The letter was received several days later and the SFPD alerted the FBI on December 29.

– The media reported the story in late December while Belli was in Europe.

– The media attention provoked the TV caller to call Belli’s home some time in January 1970.

– Belli’s housekeeper told the caller that Belli was in Europe.

– The housekeeper contacted police to report the Zodiac call.

– Shortly after receiving this information, the SFPD alerted the FBI on January 14, 1970.

– SFPD then placed a tap on Belli’s telephone and, when the man called again, they were able to trace the calls to a mental hospital and patient Eric Weill.

– On February 18, 1970, the SFPD informed the FBI that the matter had been resolved and the caller had been identified.

– The “birthday” call was forgotten because it was not made by the real Zodiac.

– An impostor called Melvin Belli’s home and declared “Today’s my birthday!” FBI files indicated that the “birthday call” occurred on or shortly before January 14, 1970. Zodiac imposter Eric Weill was born on January 10, 1940.

– The real Zodiac did not call Melvin Belli.