1 – The Book

Isn’t that what books should be about?” — Robert Graysmith

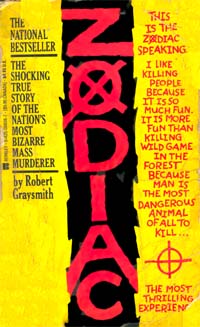

History will forever link the name of Robert Graysmith to the notorious Zodiac murders. This, of course, is no accident. For more than twenty years, Graysmith has seized every opportunity to exploit the tragedy for his own benefit. With the re-release of ZODIAC: UNMASKED, Graysmith is once again claiming that he has identified one of America’s most elusive serial killers, and once again, he is determined that the truth should not stand in his way.

Graysmith’s two books about the still-unsolved case have been widely discredited by critics, researchers, investigators, witnesses and others, yet his largely fictional accounts have served as the basis for a new major motion picture directed by David Fincher (Se7en, Fight Club). As the cartoonist-turned-crime writer is immortalized on film, audiences are entitled to know the true story behind the career and character of a Zodiac scavenger.

When the Zodiac crimes first began in the late 1960s, Robert Graysmith was a political cartoonist employed at the San Francisco Chronicle. The killer who called himself “the Zodiac” sent many letters to the Chronicle from 1969 to 1974. Graysmith was not involved in the case or the investigation.

By 1976, Graysmith obtained a copyright for his own book about the Zodiac case. In December of 1980, Graysmith had said that his book would be published by Norton and available in 1981. The last entries in Graysmith’s book are dated around this time. In 1983, columnist Herb Caen wrote an article stating that Graysmith’s book, then titled “THIS IS THE ZODIAC SPEAKING,” would be published by St. Martin’s Press and available in the fall of that year. It would be three more years before the book appeared with the title ZODIAC. When released in 1986, ZODIAC was a best seller, and became known as the definitive account of the case. However, Graysmith’s story of the Zodiac’s murders, methods and motives was incomplete, and major portions of the book are now obsolete.ZODIAC promised to present “the complete text” of the Zodiac letters, going so far as to guarantee readers, “In this book, for the first time, is every word Zodiac wrote…” On page 152, Graysmith proves otherwise. When describing the Zodiac’s thirteenth letter, Graysmith claims the letter is “reprinted completely here for the first time,” yet immediately seems to forget this promise and proceeds to delete the first portion of the text. Graysmith makes other, similar omissions throughout the book.

Graysmith claimed that investigators had escorted him to the crimes scenes to describe how the attacks had happened. Despite this assistance, Graysmith’s book inaccurately identified the locations of three of the Zodiac’s four crimes.

As an amateur sleuth, Graysmith concocted many unsubstantiated theories, including the idea that Zodiac was killing according to some astrological pattern. Graysmith told readers of ZODIAC that he had finally solved one of the Zodiac’s mysterious codes; however, FBI cryptographers stated that his solution was not valid.

Armistead Maupin, a San Francisco Chronicle columnist and author of the popular series “Tales of the City,” had been an unwitting participant in a scandal concerning a forged “Zodiac” letter. In an interview with United Press International writer Richard M. Harnett, Maupin said, “I think the public has already been terrified far too much by this boogeyman story,” and expressed concerns that Graysmith’s book would revive the hysteria surrounding the unsolved mystery. Maupin’s words proved prophetic when, shortly after the publication of Zodiac, more hoaxes and forged letters plagued police and the public.

The boogeyman story began all over again on the other side of the continent when a man responsible for several shootings in New York began to send letters to local newspapers and claimed to be the Zodiac. Police eventually captured the copycat, and a search of his belongings produced a well-thumbed copy of Graysmith’s book. Some critics argued that the crime spree might have been avoided had Graysmith not provided such a sensational and glorified portrait of the Zodiac as inspiration.

Richard Harnett’s review of Zodiac appeared in The Los Angeles Times on February 9, 1986, and offered some of the only media criticism of the book. Harnett wrote that a “good account of all the facts in the Zodiac affair would have been a valuable contribution … but Graysmith, a newspaper cartoonist, took on the role of amateur sleuth rather than historian … He neglects those parts of the historical record that don’t fit into his scenario.”

Most of Graysmith’s scenarios revolved around Arthur Leigh Allen, a convicted child molester who first came to the attention of authorities in 1971 when an estranged friend told police Allen had confessed his intent to commit crimes similar to those of the Zodiac. The former friend had once complained to Allen’s brother that the suspect had made improper advances toward his young daughter, but the friend did not reveal this allegation to police. Investigators did not question the suspect or the accuser about this possible motive to implicate Allen. The subsequent investigation by police in San Francisco and nearby Vallejo included the search of a trailer owned by Allen; however, investigators failed to uncover any evidence to link Allen to the Zodiac crimes. Allen once again came under scrutiny when the California Department of Justice conducted a review of the original Zodiac investigation, but authorities found no evidence to link Allen to the unsolved murders.

After Graysmith’s book and its thinly veiled portrait of Allen made the suspect the subject of local curiosity, another man from Allen’s past came forward and claimed Allen had confessed his intent to commit a Zodiac-like crime. Police had arrested Allen and the accuser more than 30 years earlier during a fight between the two men. The informant had committed several armed robberies and hoped to avoid a prison sentence by implicating Allen. The Vallejo police captain and a retired detective launched another investigation and eventually searched Allen’s home. This investigation also failed to connect Allen to the Zodiac crimes but Allen’s identity as the prime suspect in the unsolved murders reached the newspapers, local television news and even the syndicated tabloid shows A Current Affair and Geraldo Rivera’s Now It Can Be Told.

In interviews conducted shortly before he died in 1992, Allen repeatedly declared his innocence and complained of harassment from the police and others. News reports of Allen’s death often quoted Graysmith’s book and repeated erroneous information about the suspect, further blurring the distinction between Allen and his fictional counterpart.

Graysmith’s questionable efforts to link Allen to the crimes began in the introduction to Zodiac, where he informed readers that “one of the Zodiac’s victims may have known his true name” and “this victim, in the act of turning Zodiac into the police, had been murdered.” According to Graysmith, the victim in question, Darlene Ferrin, engaged in an intense argument with a mysterious stranger Graysmith believed to be a man identified only as “Lee,” the nickname often used by Arthur Leigh Allen. In Graysmith’s scenario, a car chase to Blue Rock Springs Park ended when the stranger approached Ferrin’s vehicle, uttered her nickname, and proceeded to open fire on the victims. Ferrin’s companion lived to tell a very different story and the original police reports effectively refute Graysmith’s version of events.

Graysmith would later claim that a witness and his sister had heard Ferrin and her killer arguing just before the shooting occurred. The witness in question never claimed to have heard such an argument and he told police a very different story. The witness did not have a sister.

2 – An Almost Completely Fictitious Person

“Starr was everywhere I looked.” – Robert Graysmith, ZODIAC

ZODIAC presents a character based entirely upon a real-life suspect named Arthur Leigh Allen. Using the pseudonym “Starr”, Graysmith creates the villain of the piece; a disturbed, violent man who is most likely responsible for the Zodiac murders, and suspected in the murders of more than 40 young women in and around Santa Rosa. “Starr” is so frightening that his own family believed he was the Zodiac and informed the police of their suspicions. Police believe “Starr” was the elusive killer, but could not find the proof they needed to put him behind bars. The book ends with the author’s conclusion that “Starr” was the Zodiac, forever damning the character to eternal infamy.

The character of Bob Hall Starr and the man known as Arthur Leigh Allen are two different people, yet, for years, the two have been synonymous to the public. Just as TV’s fugitive Doctor Richard Kimball was not Dr. Sam Shephard, and Dracula was not Vlad the Impaler, the difference between Starr and Allen lies in the gray area between fact and fiction.

Robert Graysmith based his fictional character on a real person, yet the fictional character exists in a work of nonfiction. Graysmith informed readers that he had changed the man’s name, but few were aware, or would bother to suspect, that the author had also changed the facts to suit his purposes.

The subtle and deliberate manner in which Graysmith transformed Arthur Leigh Allen’s life and person in order to give the reader the impression that he was the Zodiac is almost invisible to those who do not have access to or do not seek the facts. Relying on Graysmith to be truthful, the reader learns about Starr, and therefore, Allen, through his words. As readers are introduced to Starr, they are led down a path that has been carefully constructed by an author who was willing to distort the truth in order to convince readers that the character, and, by proxy, the suspect he represented, was the Zodiac.

The process of prejudicing the jury of readers begins on the back cover of Graysmith’s book, ZODIAC, where he promised his readers the author’s “theory of the Zodiac’s true identity,” which is based on “eight years of research” and “hundreds of facts never before released….” These claims give the author, and his conclusions, credibility.

On page 15 of ZODIAC, Graysmith introduced a mysterious stranger as a man who “frightened” Zodiac victim Darlene Ferrin in the months before her death. Several people claimed to have seen this man, but, in the decades since the crime, no one has identified this individual. According to Graysmith, Darlene was “scared to death” of the stranger, who watched her “constantly.”

On page 18, readers learned that a strange man named “Bob” had known Darlene, and that “Bob” is not the man’s real name. Later, this “Bob” will become “Starr,” and although Darlene Ferrin did know a man named “Lee,” there is no evidence that Arthur “Lee” Allen was that man. Neither “Starr,” nor Allen, matches the physical description of “Bob,” who was said to be “five feet eight inches tall or so…hair curly, wavy…dark hair…” Allen was at least six feet tall, practically bald, weighed two hundred pounds, and was 36 years old. One witness cited in ZODIAC stated that “Bob” was “thirty to twenty-eight and not heavy. He wore glasses.” Allen did not wear glasses, and was, by any definition, “heavy.”

Page 39 introduces the theory that Darlene had an argument with a “stranger” who then followed her to Blue Rock Springs Park and killed her.

Although there is no evidence that Darlene argued with such a man that night, Graysmith proceeds to tell readers that a Vallejo detective uncovered such information. In reality, police had learned that a witness had seen a waitress (not identified as Darlene Ferrin) talking to man in the parking lot of Darlene’s place of work. This event occurred the afternoon before the midnight shooting, and the witness stated that the man and woman appeared to be talking about a vehicle, not arguing as Graysmith has claimed. The description of the man seen talking to a waitress in the parking lot does not match the description of the man who shot Darlene, although Graysmith continues to imply that the two men are the same individual. The descriptions of the man who was seen talking to a waitress in the parking lot does not match the description of “Bob,” yet Graysmith continues to imply that the two men are one and the same. The description of the man who was seen talking to a waitress in the parking lot, the man who shot Darlene, and “Bob” do not match the description of “Bob Starr,” but Graysmith leads the reader to believe he is all three.

Graysmith introduced the villain of his book on page 260 as “Robert ‘Bob’ Hall Starr,” a “weird son of a bitch” who must be watched “all the time.” A brief character study of “Starr” does match Arthur Allen on several counts, including the fact that he lived with his mother in her Vallejo home at the time of the Zodiac murders. “Starr” was highly intelligent, and a loner who collects rifles and enjoys hunting.

“Starr,” like Allen, was a pedophile, and Graysmith concluded, “This would fit in with Zodiac’s knowledge of school bus routes and vacation times for kiddies.” The author does not mention that the Zodiac never demonstrated any knowledge of any bus routes, or that anyone who had attended school for at least a year would possess accurate knowledge regarding the “vacation times” of schoolchildren.

Graysmith repeats a theory that “Starr” had access to a car similar to that used by the Zodiac at the Blue Rock Springs shooting. The author appears to have had access to the police report detailing the investigation of this possibility, but neglects to mention that the same report states that police learned that Allen had most likely not used the car.

The author’s efforts to implicate his suspect continued in the years since the publication of ZODIAC. Graysmith spread an unsubstantiated rumor that Allen had received a speeding ticket near the scene of Zodiac’s Lake Berryessa attack. This rumor eventually appeared as a verified fact in a book written by former FBI profiler John Douglas.

In an article for the website APBnews.com, Graysmith claimed that excited SFPD investigators had contacted him with news that initial DNA tests had produced a positive match to Allen’s DNA. The article described a meeting in which the disappointed investigators broke the bad news that the match was a “false positive.” The investigators in question stated that no false positive match ever occurred and that the entire story is not true.

3 – The 1978 Letter

Two years after Graysmith obtained the copyright for his book, The San Francisco Chronicle received the first Zodiac letter in almost four years. Although initially deemed authentic, several handwriting experts subsequently concluded that the letter was a forgery. Graysmith claimed the letter was authentic and soon constructed an elaborate, though seriously flawed, theory to support this claim. According to Graysmith, the Zodiac used handwriting samples obtained from several different people and an enlarger/projector in order to fabricate his handwriting style.

The writing on Bryan Hartnell’s car door is unmistakably similar to the Zodiac’s handwriting, and Morrill himself concluded that the Zodiac was responsible for that message. It is unlikely, if not implausible, that the Zodiac used a projector on this occasion.

In Zodiac, Graysmith put forth the theory that Allen was the Zodiac, and, therefore, the author of the Zodiac’s many handwritten messages. He used his elaborate projector theory to explain how Allen was able to disguise his handwriting and fool document experts such as Sherwood Morrill, who was only one of several experts to conclude that Allen did not write the Zodiac letters.

Graysmith claims in one quick sentence, “Sherwood Morrill confirmed my theory.” (pg. 219). Yet he states that in 1981 he “dropped in on Sherwood Morrill “to compare handwriting of a suspect with the Zodiac’s (Zodiac, pg. 298, paperback edition). If Morrill actually believed that Graysmith’s projector theory was true, he would not continue to exclude or include suspects based on their handwriting. Graysmith seems oblivious to this blatant contradiction.

Official documents and media interviews, as well as the expert’s family, demonstrate that Morrill’s opinions never changed throughout his many years on the case. Until his death, Morrill stated that he was certain the Zodiac used his normal handwriting when writing the letters and the expert was unwavering in his belief that he could identify the killer using little more than a bank deposit slip.

Graysmith’s theories collided with modern science when the SFPD Crime Lab obtained a DNA sample from the envelope that had contained the 1978 letter and compared that sample to DNA taken from Allen shortly after his death. The samples did not match. In an article for The San Francisco Chronicle, Graysmith wondered why authorities would test a letter that everyone believed to be a forgery. An odd statement, considering that Graysmith was one of the only individuals who had been claiming that the Zodiac had actually written the 1978 letter.

Faced with handwriting and DNA evidence that excluded Allen as the author of the 1978 letter, Graysmith conveniently began to speculate that mysterious, unnamed accomplices might have written the Zodiac letters while Allen committed the actual crimes. Graysmith has quickly embraced this theory since new DNA tests on other Zodiac letters have once again excluded Allen.

By 1999, Graysmith seemed to have lost track of his multiple if ever-flexible positions on the 1978 letter. In an on-camera interview for the television program Perfect Crimes, Graysmith told viewers that “we” received a Zodiac letter on the day after Allen was released from Atascadero. Allen was released from Atascadero in August of 1977. The letter in question arrived at the offices of The San Francisco Chronicle in April of 1978.

In the years since its publication in 1986, Zodiac has become a true crime legend often referred to as a “classic.” Graysmith’s version of the Zodiac story was adapted for the big screen in David Fincher’s 2007 film Zodiac. Like its source material, the film presented a largely fictional version of the story and abused the facts in order to make Arthur Leigh Allen seem like the most likely suspect. The movie also relied on Graysmith’s sequel titled Zodiac Unmasked, published in 2002. Like its predecessor, the book departed from the facts in order to convict Allen in the court of public opinion.

Read more about Robert Graysmith’s ZODIAC UNMASKED